Following is a behind-the-scenes story by my husband, Sam Harrington, a former gastroenterologist and soon-to-be published author of At Peace: Choosing a Good Death After a Long Life. His book about end-of-life decision making for the elderly will be published in Feb. 2018 by Hachette Book Group. Initially, he and I worked together on his book. I was his editor and book coach, editing dozens of his early blog posts to help him write more clearly and cleanly. I helped him organize his book and edited the first few chapters. Then, we decided it was more important to stay married… Read on for Sam’s almost five year journey from blogging to conception of the book to publication with one of the Big 5. – DW

Debbie has asked me to muse on the experience of a first-time author from the point of view of someone who “trained” as a writer by doing thousands of colonoscopies. For 31 years, I limited my writing to the required medical reports. Then in 2013 I left my medical practice and we left Washington D.C. to move to the coast of Maine.

Debbie has asked me to muse on the experience of a first-time author from the point of view of someone who “trained” as a writer by doing thousands of colonoscopies. For 31 years, I limited my writing to the required medical reports. Then in 2013 I left my medical practice and we left Washington D.C. to move to the coast of Maine.

Using our joint blog, Gap Year After Sixty, as a platform, I started writing blog posts about the excesses of modern medicine. I also took time for longer visits with my aging and ailing father. Eighteen months of blogging and thinking passed.

At some point I realized that these two subjects dovetailed into one. I wanted to help older patients to foresee the course of their illnesses and to avoid excessive and futile treatments. And I wanted to tell my father’s story as a way to illustrate a good (or relatively good) death. I had a message. I had the beginning of a book. And yet, I had no idea what I was getting into, nor how long it would take.

Yes, a book was on my bucket list

Debbie has asked me if I had thought previously about writing a book. I guess I had, although she says I never mentioned it to her during my decades of practicing medicine. The answer is, “Yes, I had long thought about writing a book.” The reasons are twofold but complicated. First, I had a message. I had something responsible and unselfish to say.

Second, I wanted to do something bigger than simply practice good medicine. I had benefited by every educational advantage and opportunity and I wanted to do something more than simply retire. And in some way, I wanted to thank my parents for investing so much in me. And yet, as an individual, I was afraid to stick out my neck and take a public stand. I come from a family of reticent people.

The fateful whiteboard session with Debbie

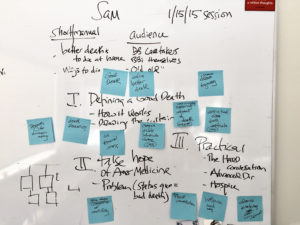

After writing several dozen blog posts, as well as several potential chapters, I asked Debbie for a brainstorming session. I remember it well. We sat down in her office in Maine in January 2015, looking out over fresh snow on the lawns leading down to the ocean. She took out a black marker and a pad of blue stickies and started scribbling on her giant whiteboard. We talked about the audience for the book. At the time I had not focused on defining the audience, thinking it was self-evident.

After writing several dozen blog posts, as well as several potential chapters, I asked Debbie for a brainstorming session. I remember it well. We sat down in her office in Maine in January 2015, looking out over fresh snow on the lawns leading down to the ocean. She took out a black marker and a pad of blue stickies and started scribbling on her giant whiteboard. We talked about the audience for the book. At the time I had not focused on defining the audience, thinking it was self-evident.

But Debbie pressed the issue, as did every subsequent coach, agent, and editor. It was clear to me that my core audience was made up of patients over the age of 65. It became clear over time that the audience should also include everyone engaged with that core group: family members, caregivers, elder care lawyers, hospice personnel, home care personnel, and primary care medical personnel.

In retrospect, defining the audience at multiple steps along the process helped refocus and refine the book.

I wanted to divide the book into thirds, each with four or five chapters. Debbie said, “Great idea. You can decide later what order they go in.” The first third was to expose the reader to the truth about the American health care system (it’s not set up to help the elderly). The second third was to educate the reader about the most common diseases afflicting the elderly. And the final third was to explain what to do about it all.

Talking through everything I wanted to cover in the book, we assigned topics to each of the chapters. And we discussed how I could use the story of my father’s decline and death (and earlier, my mother’s) as a common thread to weave it all together. At that moment, my father was still living, quietly, in hospice care. I did not know how – or when – things would end for him.

However, I went off and started pounding out chapters on the disease topics, figuring that I could add the emotional story line later.

Adding my father’s story after he died

When my father died at ninety-four in April 2015, I had a surprising and sudden burst of energy at the keyboard. I felt I could add his story line without worrying about what he might think. By June 2015, I felt that I had a book. I went back to Debbie for more help. She was confident that I had several good chapters (in fact, she had already suggested that my draft was good enough for a traditional publisher) but she felt other sections needed a lot of work. I wasn’t really ready to hear that. After some animated discussions that only a husband and wife can understand, we decided that I needed another book coach – someone to whom I was not married.

Another Debbie, another book coach

Debbie connected me with her friend and book coach, Debbie Reber. Later in June, Debbie-2 and I established a formal understanding and with her help I shaped up the weak chapters. By then it was September 2015. Debbie-1 and Debbie-2 both agreed the book had the potential to appeal to a traditional publisher. This meant that I needed a formal book proposal. Debbie-1 made contact with her literary agent while Debbie-2 helped me write and organize the book proposal.

This proved to be a considerable undertaking – 140 pages. Who knew that book proposals were mini books? My book proposal consisted of an introduction, a summary, several sample chapters, chapter summaries, a description of the potential market, a list of competitive books (and why mine was different), a promotional plan, and an “about the author” section. This sounds daunting but it is the accepted template for what makes up a book proposal.

Most important, I learned that the book proposal was much harder than a first draft. It has to be very well written and edited because it is designed to appeal to an audience of one – a publisher willing to take a risk on you, the author.

By December 2015 my work with Debbie-2 was successfully completed and Debbie-1 had reconnected me with her literary agent, Elizabeth Wales, with whom we had both gone to high school. Elizabeth was interested in the book proposal and felt she could find a traditional publisher. At this point, I signed a letter of agreement with Elizabeth to be my agent. (I am telling you this to illustrate that there is a sequence of prescribed steps leading up to a traditional book contract.)

Take out the “Doctor-speak”!

By April 2016, under Elizabeth’s guidance, I had rewritten the book proposal in her vision to make it more salable. With particular attention to the sample chapters and the overview she had me soften my tone, translate my medical terminology, and dampen my professional voice (Both my Debbie’s, and Elizabeth, were telling me to: “Take out the Doctor-speak!”). In May and June of 2016, Elizabeth was ready to send it to a variety of New York publishers.

By late June 2016, Karen Murgolo, vice president and editor of Hachette’s Grand Central Life & Style imprint, picked up my book, offering me a modest five-figure advance. (This was wonderfully validating even though it wasn’t a huge amount of money.) She was the only editor who saw how my book was different from Atul Gawande’s blockbuster, Being Mortal, and that is because her mother had recently passed away. She told me, after reading the book proposal, that if she had been able to read At Peace, she would have made better decisions about her mother’s end-of-life care.

Finally, a book contract! Then more rewriting…

By July 2016 I had a signed contract with Hachette, with the final manuscript to be submitted by April 2017. If you’re doing the math on the timeline, you’ll note that I had been effectively “writing” the book for almost two years, from the beginning of the idea to the signed contract.

By July 2016 I had a signed contract with Hachette, with the final manuscript to be submitted by April 2017. If you’re doing the math on the timeline, you’ll note that I had been effectively “writing” the book for almost two years, from the beginning of the idea to the signed contract.

It wasn’t over.

Now I began rewriting and re-organizing the entire book under Elizabeth’s continued guidance and with Karen’s editing. I added endnotes (painstaking and time-consuming). I obtained permission to use charts, graphs, and certain quotes. I asked one of my physician daughters, who is also an artist, to draw the charts. Then I used a graphic designer to turn her sketches into high-resolution files.

The publisher chose the title and the sub-title and designed a cover. I liked them. I had the ability to push back but I didn’t need or want to.

But there were frustrating weeks of waiting. Because traditional publishers are so busy with multiple book projects, they have a complicated schedule and can only spend a limited amount of time with any one author. Therefore, I would write and revise for a few weeks and then wait several more weeks for edits before proceeding with the next phase.

Debbie-1 assured me that this timing was normal. Other first-time authors might find these pauses to be a welcome relief. Perhaps it was my get-it-done approach acquired through decades of medical training and practice but I found these periods of waiting for feedback to be painful.

And there was more to come. After I submitted the book manuscript there would be an additional ten months of copyediting, galley editing, and promotional work. In this era of instant gratification, coupled with a physician’s need for control, waiting for validation from my editors and others (including media and “influencers”) has been particularly challenging.

Manuscript submitted and accepted

If I haven’t made it clear, I’m not a procrastinator so I easily made the April 3, 2017 deadline for the final manuscript. It was officially “accepted” by my editor – one of the milestones in traditional publishing. (If the editor rejects it, you have to go back and revise some more.) Since then I have been reviewing and responding to Hachette’s detailed copyediting changes, first in a Word document and then in what are called the galleys. These are the typeset book pages delivered as a PDF and also in a stack of printed 8 ½ by 11-inch paper.

Almost five years from beginning to publication

As I write, I’m continuing to work on details of my promotional plan for the pub date (that’s publisher lingo) of February 6, 2018. It has been a long haul. It will be almost five years from initial blog posts, to conception of the book, to publication day. Exciting as writing and publishing a book sounds, it has been an emotional trial. After 31 years as a practicing physician, I am suffering terribly from imposter syndrome as I start a whole new career as an author. But the book has been a positive challenge and a wholly worthwhile undertaking. I can’t wait to get my message out!

My message, distilled

If you can accept that you’re going to die, you can choose a good death.

In my book I help the reader understand the reality of the U.S. medical system, the major diseases that people die from, what performance status means and why it is so important, and what your prognosis is after age 65. Accepting that you’re going to die is not an easy truth for many of us. When you do, you can plan and choose a good death.

Please visit my new site at samharrington.com where you can read the Introduction and learn more. – Sam Harrington

Sam’s bio

An honors graduate of Harvard College and the University of Wisconsin Medical School, Sam Harrington practiced internal medicine and gastroenterology for more than 30 years in Washington, D.C. His work as Sibley Memorial Hospital’s patient safety officer representative to the Johns Hopkins Medicine Board of Trustees and his service on the board of trustees of a nonprofit hospice in Washington D.C. brought him into the discussion of end-of-life medical care.

To pre-order Sam’s book

Visit his new website at samharrington.com or pre-order directly from Amazon.

Read our blog

Read both Sam’s and Debbie’s writing on reinventing life after 60 at Gap Year After Sixty.